Spirituality of the Flesh

Exploring the obscure history and spirituality of the flagellants of northern New Mexico.

Would mysticism exist without the presence of the flesh? If you didn't have a body, then you wouldn't be able to experience divine intervention upon it. Spiritualists may decry the flesh and the sins that come along with it, but the mystics and stigmatics depend on it as evidence for glimpses of the kingdom of God. Even if most fleshly interactions with divinity only brought pain and suffering, it was all given up in service to a higher power. The experience of pain was considered a blessing because that was the way to know God's presence: through the feeling of pain and the evidence of wounds. It's surprising, then that most rationalists would be so against this kind of fleshly spirituality. If knowledge can be derived from empirical data gathered through observation and experience, then mysticism is a form of knowledge production. The majority of the Westernized world do not think this way, of course. At best they treat any mystical spirituality as something quaint and "primitive," at worst they use the mystic's belief system against him to ascertain dominance.

Flagellation, or mortification, is a spiritual practice that originated in (and was later suppressed by) the Roman Catholic Church around the 13th Century. It started in medieval Italy and Spain, but had spread across Europe. Even Martin Luther kept a whip for self-flagellation. For these practitioners, mortifying the flesh was a way to connect to God by emulating the suffering endured by Christ on Good Friday. The suffering is also offered up to God as part of a repentance scheme and framed as an act of extreme piety. As quickly as the movement spread it died down again thanks to the Pope denouncing it as a heresy. Practitioners seemingly disappeared, but there were secret underground orders such as Los Hermanos de la Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno. Popularly known by a simpler name, the Penitentes, this sect of flagellants made their way outside of Spain to colonial America and landed in northern New Mexico and parts of Southern Colorado, where they still reside as a semi-secret society.

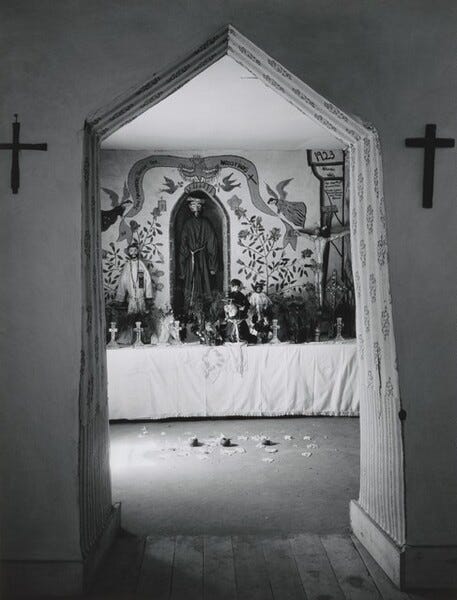

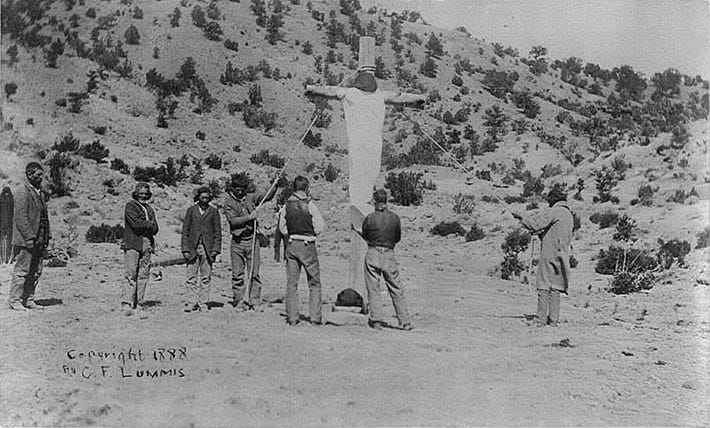

The Penitentes have rich culture-ways and traditions that have survived suppression, abandonment, and scrutiny. In the deserts of New Mexico, they have countless adobe structures built (called moradas) for their initiation rites and Lenten services. These adobes are stout and unassuming, and nearly always windowless—if there are windows, they are typically boarded up. This spirituality's approach to aesthetics already looks very different from the typical Roman Catholic cathedral built tall enough to reach the heavens with clerestory lighting and stained glass windows crafted to glorify the heavens. If the cathedral is the materialist's way to God, then the morada beckons a pure spiritualist. In a weird way, this feels inverse and counterintuitive. The Penitentes, though secret, can be heard throughout a small enough New Mexican village when they sing their alabados. The songs are mostly psalms or adapted psalms sung in medieval Spanish dialect. Though the language and tradition is Spanish, they have evolved syncretically with indigenous chants particular to the Pueblo people of northern New Mexico. Overall, their spirituality resembles any other kind of Catholic / Christian sect, except for their devotion to the flesh, and, in particular, harming of the flesh. Flagellants often create sacred whips called "disciplines" with spikes on the end; the Penitentes in New Mexico will often harvest cactus and attach those as the tips of the whips they use for self-mortification. In Lent things get ramped up further. To suffer alongside Christ, the Penitentes will process up a hill with a large wooden cross on Good Friday. Every year a chosen man from the brotherhood will be "crucified" (wrists are tied to the cross beams) on the cross while the others observe, sing, and pray.

When Mexico gained independence from Spain and the New Mexico region was invaded by the United States and made into a territory, the area was spiritually abandoned. The Spanish priests fled the area, and a scant few American diocesan priests occupied major cities such as Santa Fe and Albuquerque. The Penitentes and their rituals filled a spiritual gap in the mountain villages. But, the archbishops that were sent by the American arm of the Roman Catholic Church tried very hard to "Americanize" the region. In the 19th Century, another suppression of the flagellants was taking place, but it was largely unsuccessful, especially after New Mexico became a ratified state in the Union. In the early 1900's the great migration of East Coast artists, musicians, poets, writers, etc. to northern New Mexico brought a curious gaze to the Penitentes. Cultural anthropologists and ethnographers gained the trust of the Penitentes only to expose them and their sacred societies in textbooks later on. The exposure went further into the art world as well when photographers such as Ansel Adams made photographs of their rituals and moradas.

"Descendants" of the Enlightenment will read about and gaze upon the Penitentes with earnest interest and think that the practice is antiquated mysticism. While it is true that the fleshly spiritualism is the most interesting aspect of their practice, it is not the only thing that makes up their ongoing ministry. The Penitentes are spiritual community leaders who care for the sick and dying, take in orphans in need of shelter, and provide charity work for the poor. They come to the same altruistic conclusions as mainstream Catholic Christians, but why the denunciation by the official Church doctrine? I think maybe the self-flagellation is a radical exercise in body sovereignty. That mysticism allows one to connect to divinity in a purely individual way. The knowledge that God exists doesn't reside in the indulgences you pay, or the cathedrals you build, but in the skin and blood and fascia that is yours for a limited time on this earthly plane.

>Would mysticism exist without the presence of the flesh?

Blessed souls can enjoy the beatific vision without a body, so yes. Mysticism is primarily spiritual, although not exclusively—IIRC one of the Psalms involves David writing about how his very flesh rejoices in the lord.

And I'm not sure if self-flagellation has been suppressed... St. Pope John Paul II had a discipline which he'd beat himself with, and members of Opus Dei do stuff like that to this day.

But even what is good is not always prudent. American bishops probably tried to suppress the practice because they were worried about the penitentes alienating the WASPS through a practice which admittedly strikes the modern mind as medieval in the worst way, and deeply retrograde. But while jarring (like the veneration of bones), the practice, when not exaggerated, can be a good aid to a person's holiness. Not that I would know from personal experience. But too many saints have sworn by it for it to be a bad thing (not to mention the precedent in scripture: 1 Cor 9:27). Not that it's mandatory either. If I'm not mistaken, the practice is basically unheard of in eastern Christianity (they prefer to fast).

Very cool! Where did you learn about this?